![]()

Charles Babbage died in 1871. He commenced the Difference Engine about 1822, and the Government abandoned it in 1842. He commenced the Analytical Engine about 1833.

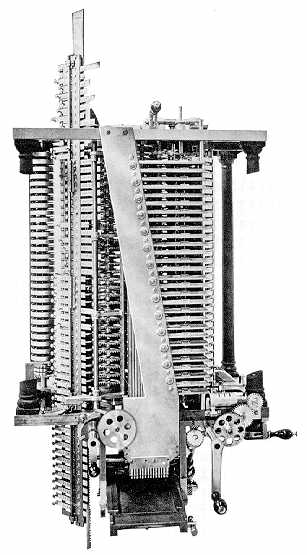

A few years before his death he began to execute in metal that part which he called the “Mill,” where the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division can be performed.

I will give here an extract from Part II. of his Essay towards the Calculus of Functions, 1816, because it shows the working of his mind at that time, which further on led him to devote his life to the perfection of machinery for the numerical solution of Functions arrived at by mathematical analysis:—

“My subsequent inquiries have produced several new methods of solving functional equations containing only one variable quantity and much more complicated, and have convinced me of the importance of the Calculus, particularly as an instrument of discovery in the more difficult branches of analysis. Nor is it only in the recesses of this abstract science that its advantages will be felt: it is peculiarly adapted to the discovery of those laws of action by which one particle of matter attracts or repels another of the same or a different species; consequently it may be applied to every branch of natural philosophy, where the object is to discover by calculation from the results of experiment the laws which regulate the action of the ultimate particles of bodies. To the accomplishment of these desirable purposes, it must be confessed that it is in its present state unequal; but should the labours of future inquirers give to it that perfection which other methods of investigation have attained, it is not too much to hope that its maturer age shall unveil the hidden laws which govern the phenomena of magnetic, electric, or even of chemical action.”

To which I would add also the laws which govern our Cosmos, the leading object of this Society.

By his will he left all that existed of his analytical engine, its drawings and notations, as well as his workshop and tools, to me, his youngest son. I was at that time on furlough in England, and after his death I endeavoured to complete the work as far as the instructions in the hands of the workmen admitted, and in that state it remains in the South Kensington Museum at the present day.

I had to return to India at the end of my leave, but retired from the Indian Service in 1874.

Among the things which came to me in his will there was a large number of pieces fitted and ready for the difference engine; but many of the frame plates had been cut up and used by my father for experimental work. I thought to replace them and put together what existed. 1 began by having plates made to complete the framework as originally designed, and to put in their places the pieces, some completely finished and others less so. I also contrived a new driving gear which answered perfectly, but I found the expenses heavy and the utility doubtful, and about 1879, not knowing what to do with it, I sent the whole (excepting five or six small pieces sent to different places) to the melting-pot.

About that time I heard that Mr. Wilkinson, a nephew and successor of Clement, had broken up his workshop and melted up what remained there of the unfinished pieces of the difference engine. Had I known this in time I might have kept what I had, for I still hold to the opinion expressed in Babbage's Calculating Engine, published in 1889, that the calculating part of the difference engine might have been completed, at the time the Government gave it up, for, say, £500.

In 1856 I turned my attention to the machine of the Messrs. Schentz,

and, with a view of instructing myself, I applied my father's system

of Mechanical Notation to their machine. My father was very pleased

with my work, and sent me to exhibit my diagrams at the meeting of the

British Association at Glasgow. The diagrams are now in the South

Kensington Museum, and I have employed the notation for the present

machine, and have found it very useful.

In 1856 I turned my attention to the machine of the Messrs. Schentz,

and, with a view of instructing myself, I applied my father's system

of Mechanical Notation to their machine. My father was very pleased

with my work, and sent me to exhibit my diagrams at the meeting of the

British Association at Glasgow. The diagrams are now in the South

Kensington Museum, and I have employed the notation for the present

machine, and have found it very useful.

Soon after my return to England I began to think that I might be able to complete the “Mill,” not as part of the larger machine which my father proposed, but something which would be practically useful by itself in the hands of a skilled operator.

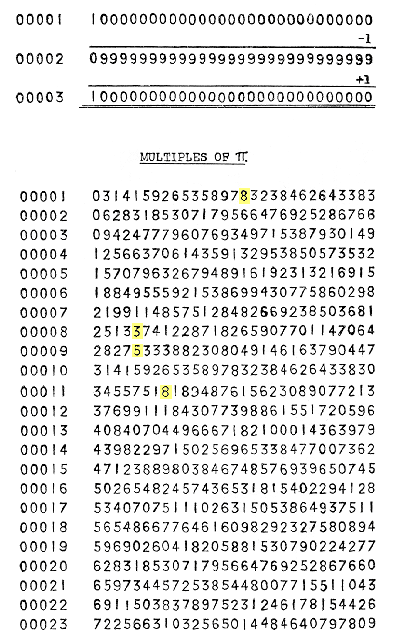

The iron top and bottom frame plates were cast in 1880, and the work was carried on, somewhat intermittently, until the 21st. of January 1888, when the machine produced a table from 1st. to 44th. multiples of π to twenty-nine places of figures, which could have been prolonged indefinitely; but the machinery did not work smoothly, and in the 32nd. multiple of π the carriage had failed and a figure had gone wrong. For a time I was discouraged, and in 1896 circumstances led me to discontinue the work, and I turned to other less expensive pursuits and offered the unfinished work of my father, with all the drawings and papers belonging to it, as well as my own imperfect work, to the South Kensington Museum, and the offer was accepted.

In 1906 my attention was accidentally attracted to my work. I saw

what was amiss and the way to remedy it, with the result that it was

sent to the factory of Mr. R. W. Munro at Tottenham, and, under my

close supervision, it has been completed and the apparatus made to

print the calculated results on paper, from which a zinc block has

been made.

The printed calculations which follow are specimens of its work.¹

Cheltenham:

1910 April 8.

¹ It will be seen that the "multiples of π" are really multiples of the first 29 digits of π.

The Secretaries are indebted to several correspondents for pointing out errata in the facsimile of work produced by General Babbage's calculating machine (M.N., vol. lxx. p. 520).

These errors are not entirely the same as certain errors in the facsimile sheet distributed by General Babbage at the meeting.

General Babbage has kindly given the following explanation of this.

Two separate calculations A and B were made on the machine while it stood in the maker's shops, and several mistakes occurred.

The failure in printing was due to weakness in certain springs, which had been strengthened before the machine was exhibited; thus the printed figures did not agree with the calculated.

The following corrections should be made in the facsimile printed in the M.N.

In π: Read 3.141592653589793, and carry corresponding correction throughout.

In 8π: Read 25132.

" 9π: " 28274.

" 11π: " 34557519.

![]()