Books by Mahon, Basil

- Mahon, Basil.

The Forgotten Genius of Oliver Heaviside.

Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2017.

ISBN 978-1-63388-331-4.

-

At age eleven, in 1861, young Oliver Heaviside's family,

supported by his father's irregular income as an engraver of

woodblock illustrations for publications (an art beginning to be

threatened by the advent of photography) and a day school for

girls operated by his mother in the family's house, received a

small legacy which allowed them to move to a better part of

London and enroll Oliver in the prestigious Camden House School,

where he ranked among the top of his class, taking thirteen

subjects including Latin, English, mathematics, French, physics,

and chemistry. His independent nature and iconoclastic views

had already begun to manifest themselves: despite being an

excellent student he dismissed the teaching of Euclid's geometry

in mathematics and English rules of grammar as worthless. He

believed that both mathematics and language were best learned,

as he wrote decades later, “observationally,

descriptively, and experimentally.” These principles

would guide his career throughout his life.

At age fifteen he took the College of Perceptors examination,

the equivalent of today's A Levels. He was the

youngest of the 538 candidates to take the examination and

scored fifth overall and first in the natural sciences. This

would easily have qualified him for admission to university,

but family finances ruled that out. He decided to

study on his own at home for two years and then seek a job,

perhaps in the burgeoning telegraph industry. He would receive

no further formal education after the age of fifteen.

His mother's elder sister had married

Charles

Wheatstone, a successful and wealthy scientist, inventor,

and entrepreneur whose inventions include the concertina,

the stereoscope, and the Playfair encryption cipher, and who

made major contributions to the development of telegraphy.

Wheatstone took an interest in his bright nephew, and guided

his self-studies after leaving school, encouraging him

to master the Morse code and the German and Danish languages.

Oliver's favourite destination was the library, which he later

described as “a journey into strange lands to go a

book-tasting”. He read the original works of

Newton, Laplace, and other “stupendous names”

and discovered that with sufficient diligence he could

figure them out on his own.

At age eighteen, he took a job as an assistant to his older

brother Arthur, well-established as a telegraph engineer in

Newcastle. Shortly thereafter, probably on the recommendation

of Wheatstone, he was hired by the just-formed

Danish-Norwegian-English Telegraph Company as a telegraph

operator at a salary of £150 per year (around £12000

in today's money). The company was about to inaugurate a cable

under the North Sea between England and Denmark, and Oliver set

off to Jutland to take up his new post. Long distance telegraphy

via undersea cables was the technological frontier at the time—the

first successful transatlantic cable had only gone into

service two years earlier, and connecting the continents into

a world-wide web of rapid information transfer was the

booming high-technology industry of the age. While the job

of telegraph operator might seem a routine clerical task,

the élite who operated the undersea cables worked in

an environment akin to an electrical research laboratory,

trying to wring the best performance (words per minute) from

the finicky and unreliable technology.

Heaviside prospered in the new job, and after a merger

was promoted to chief operator at a salary of £175

per year and transferred back to England, at Newcastle.

At the time, undersea cables were unreliable. It was not

uncommon for the signal on a cable to fade and then die

completely, most often due to a short circuit caused by failure

of the

gutta-percha

insulation between the copper conductor and the iron sheath

surrounding it. When a cable failed, there was no alternative

but to send out a ship which would find the cable with a

grappling hook, haul it up to the surface, cut it, and test

whether the short was to the east or west of the ship's

position (the cable would work in the good direction but

fail in that containing the short. Then the cable would be

re-spliced, dropped back to the bottom, and the ship would

set off in the direction of the short to repeat the exercise

over and over until, by a process similar to

binary

search, the location of the fault was narrowed down and

that section of the cable replaced. This was time consuming

and potentially hazardous given the North Sea's propensity

for storms, and while the cable remained out of service it

made no money for the telegraph company.

Heaviside, who continued his self-study and frequented the

library when not at work, realised that knowing the resistance

and length of the functioning cable, which could be easily

measured, it would be possible to estimate the location of

the short simply by measuring the resistance of the cable

from each end after the short appeared. He was able to

cancel out the resistance of the fault, creating a quadratic

equation which could be solved for its location. The first

time he applied this technique his bosses were sceptical,

but when the ship was sent out to the location he

predicted, 114 miles from the English coast, they quickly

found the short circuit.

At the time, most workers in electricity had little use for

mathematics: their trade journal, The Electrician

(which would later publish much of Heaviside's work) wrote in

1861, “In electricity there is seldom any need of

mathematical or other abstractions; and although the use of

formulæ may in some instances be a convenience, they may

for all practical purpose be dispensed with.” Heaviside

demurred: while sharing disdain for abstraction for its own

sake, he valued mathematics as a powerful tool to understand

the behaviour of electricity and attack problems of

great practical importance, such as the ability to send

multiple messages at once on the same telegraphic line and

increase the transmission speed on long undersea cable links

(while a skilled telegraph operator could send traffic

at thirty words per minute on intercity land lines,

the transatlantic cable could run no faster than eight words

per minute). He plunged into calculus and differential

equations, adding them to his intellectual armamentarium.

He began his own investigations and experiments and began

to publish his results, first in English Mechanic,

and then, in 1873, the prestigious Philosophical

Magazine, where his work drew the attention of two of

the most eminent workers in electricity:

William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) and

James Clerk Maxwell. Maxwell would go on

to cite Heaviside's paper on the Wheatstone Bridge in

the second edition of his Treatise on Electricity

and Magnetism, the foundation of the classical

theory of electromagnetism, considered by many the greatest

work of science since Newton's Principia,

and still in print today. Heady stuff, indeed, for a

twenty-two year old telegraph operator who had never set

foot inside an institution of higher education.

Heaviside regarded Maxwell's Treatise as the

path to understanding the mysteries of electricity he

encountered in his practical work and vowed to master it.

It would take him nine years and change his life. He

would become one of the first and foremost of the

“Maxwellians”, a small group including

Heaviside, George FitzGerald, Heinrich Hertz, and Oliver

Lodge, who fully grasped Maxwell's abstract and highly

mathematical theory (which, like many subsequent milestones

in theoretical physics, predicted the results of experiments

without providing a mechanism to explain them, such as

earlier concepts like an “electric fluid” or

William Thomson's intricate mechanical models of the

“luminiferous ether”) and built upon its

foundations to discover and explain phenomena unknown

to Maxwell (who would die in 1879 at the age of just 48).

While pursuing his theoretical explorations and publishing

papers, Heaviside tackled some of the main practical problems

in telegraphy. Foremost among these was “duplex

telegraphy”: sending messages in each direction

simultaneously on a single telegraph wire. He invented a

new technique and was even able to send two

messages at the same time in both directions as fast as

the operators could send them. This had the potential

to boost the revenue from a single installed line by

a factor of four. Oliver published his invention, and in

doing so made an enemy of William Preece, a senior engineer

at the Post Office telegraph department, who had invented

and previously published his own duplex system (which would

not work), that was not acknowledged in Heaviside's paper.

This would start a feud between Heaviside and Preece

which would last the rest of their lives and, on several

occasions, thwart Heaviside's ambition to have his work

accepted by mainstream researchers. When he applied to

join the Society of Telegraph Engineers, he was rejected

on the grounds that membership was not open to “clerks”.

He saw the hand of Preece and his cronies at the Post Office

behind this and eventually turned to William Thomson to

back his membership, which was finally granted.

By 1874, telegraphy had become a big business and the work

was increasingly routine. In 1870, the Post Office had

taken over all domestic telegraph service in Britain and,

as government is wont to do, largely stifled innovation and

experimentation. Even at privately-owned international

carriers like Oliver's employer, operators were no longer

concerned with the technical aspects of the work but rather

tending automated sending and receiving equipment. There

was little interest in the kind of work Oliver wanted to do:

exploring the new horizons opened up by Maxwell's work. He

decided it was time to move on. So, he quit his job, moved

back in with his parents in London, and opted for a life

as an independent, unaffiliated researcher, supporting himself

purely by payments for his publications.

With the duplex problem solved, the largest problem that

remained for telegraphy was the slow transmission speed on long

lines, especially submarine cables. The advent of the telephone

in the 1870s would increase the need to address this problem.

While telegraphic transmission on a long line slowed down the

speed at which a message could be sent, with the telephone voice

became increasingly distorted the longer the line, to the point

where, after around 100 miles, it was incomprehensible. Until

this was understood and a solution found, telephone service

would be restricted to local areas.

Many of the early workers in electricity thought of it as

something like a fluid, where current flowed through a wire like

water through a pipe. This approximation is more or less

correct when current flow is constant, as in a direct current

generator powering electric lights, but when current is varying

a much more complex set of phenomena become manifest which

require Maxwell's theory to fully describe. Pioneers of

telegraphy thought of their wires as sending direct

current which was simply switched off and on by the sender's

key, but of course the transmission as a whole was a varying

current, jumping back and forth between zero and full current at

each make or break of the key contacts. When these transitions

are modelled in Maxwell's theory, one finds that, depending upon

the physical properties of the transmission line (its

resistance, inductance, capacitance, and leakage between the

conductors) different frequencies propagate

along the line at different speeds. The sharp on/off

transitions in telegraphy can be thought of,

by Fourier

transform, as the sum of a wide band of frequencies,

with the result that, when each propagates at a different

speed, a short, sharp pulse sent by the key will, at

the other end of the long line, be “smeared out”

into an extended bump with a slow rise to a peak and then

decay back to zero. Above a certain speed, adjacent dots and dashes

will run into one another and the message will be undecipherable

at the receiving end. This is why operators on the transatlantic

cables had to send at the painfully slow speed of eight words

per minute.

In telephony, it's much worse because human speech is composed

of a broad band of frequencies, and the frequencies involved

(typically up to around 3400 cycles per second) are much

higher than the off/on speeds in telegraphy. The smearing

out or dispersion as frequencies are transmitted at

different speeds results in distortion which renders the voice

signal incomprehensible beyond a certain distance.

In the mid-1850s, during development of the first transatlantic

cable, William Thomson had developed a theory called the

“KR law” which predicted the transmission speed

along a cable based upon its resistance and capacitance.

Thomson was aware that other effects existed, but without

Maxwell's theory (which would not be published in its

final form until 1873), he lacked the mathematical tools

to analyse them. The KR theory, which produced results

that predicted the behaviour of the transatlantic cable

reasonably well, held out little hope for improvement:

decreasing the resistance and capacitance of the cable would

dramatically increase its cost per unit length.

Heaviside undertook to analyse what is now called the

transmission line

problem using the full Maxwell theory and, in 1878, published

the general theory of propagation of alternating current through

transmission lines, what are now called the

telegrapher's

equations. Because he took resistance, capacitance,

inductance, and leakage all into account and thus modelled both

the electric and magnetic field created around the wire by the

changing current, he showed that by balancing these four

properties it was possible to design a transmission

line which would transmit all frequencies at the same speed. In

other words, this balanced transmission line would behave for

alternating current (including the range of frequencies in a

voice signal) just like a simple wire did for direct current:

the signal would be attenuated (reduced in amplitude) with

distance but not distorted.

In an 1887 paper, he further showed that existing telegraph

and telephone lines could be made nearly distortionless by

adding

loading coils

to increase the inductance at points along the line (as long as

the distance between adjacent coils is small compared to the

wavelength of the highest frequency carried by the line). This

got him into another battle with William Preece, whose incorrect

theory attributed distortion to inductance and advocated

minimising self-inductance in long lines. Preece moved to block

publication of Heaviside's work, with the result that the paper

on distortionless telephony, published in The

Electrician, was largely ignored. It was not until 1897

that AT&T in the United States commissioned a study of

Heaviside's work, leading to patents eventually worth millions.

The credit, and financial reward, went to Professor Michael

Pupin of Columbia University, who became another of Heaviside's

life-long enemies.

You might wonder why what seems such a simple result (which can

be written in modern notation as the equation

L/R = C/G)

which had such immediate technological utlilty eluded

so many people for so long (recall that the problem with

slow transmission on the transatlantic cable had been observed

since the 1850s). The reason is the complexity of Maxwell's

theory and the formidably difficult notation in which it

was expressed. Oliver Heaviside spent nine years

fully internalising the theory and its implications, and

he was one of only a handful of people who had done so and,

perhaps, the only one grounded in practical applications such

as telegraphy and telephony. Concurrent with his work on

transmission line theory, he invented the mathematical

field of

vector

calculus and, in 1884, reformulated Maxwell's original

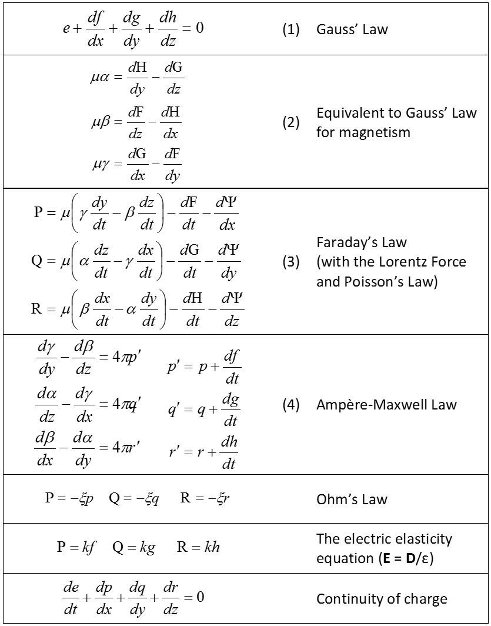

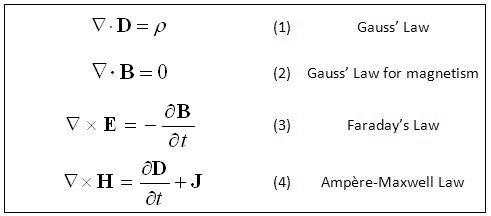

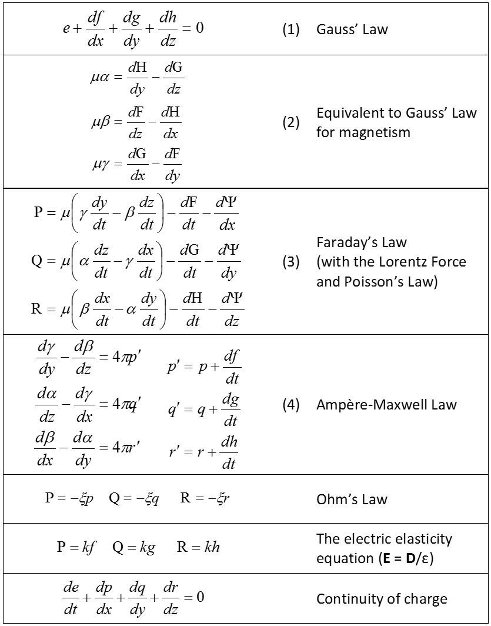

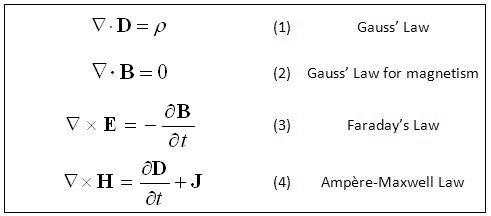

theory which, written in modern notation less

cumbersome than that employed by Maxwell, looks like:

into the four famous vector equations we today think of

as Maxwell's.

into the four famous vector equations we today think of

as Maxwell's.

These are not only simpler, condensing twenty equations to

just four, but provide (once you learn the notation and

meanings of the variables) an intuitive sense for what is

going on. This made, for the first time, Maxwell's theory

accessible to working physicists and engineers interested

in getting the answer out rather than spending years

studying an arcane theory. (Vector calculus was

independently invented at the same time by the American

J. Willard Gibbs. Heaviside and Gibbs both acknowledged

the work of the other and there was no priority dispute.

The notation we use today is that of Gibbs, but the

mathematical content of the two formulations is

essentially identical.)

And, during the same decade of the 1880s, Heaviside

invented the

operational

calculus, a method of calculation which reduces the solution

of complicated problems involving differential equations to

simple algebra. Heaviside was able to solve so many problems

which others couldn't because he was using powerful computational

tools they had not yet adopted. The situation was similar to

that of Isaac Newton who was effortlessly solving problems

such as the

brachistochrone

using the calculus he'd invented while his contemporaries

struggled with more cumbersome methods. Some of the things

Heaviside did in the operational calculus, such as cancel

derivative signs in equations and take the square root of a

derivative sign made rigorous mathematicians shudder but, hey,

it worked and that was good enough for Heaviside and the many

engineers and applied mathematicians who adopted his methods.

(In the 1920s, pure mathematicians used the theory of

Laplace transforms

to reformulate the operational calculus in a rigorous manner,

but this was decades after Heaviside's work and long after

engineers were routinely using it in their calculations.)

Heaviside's intuitive grasp of electromagnetism and powerful

computational techniques placed him in the forefront of

exploration of the field. He calculated the electric field of

a moving charged particle and found it contracted in the

direction of motion, foreshadowing the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction

which would figure in Einstein's

special relativity. In 1889

he computed the force on a point charge moving in an electromagnetic

field, which is now called the

Lorentz force

after Hendrik Lorentz who independently discovered it six years

later. He predicted that a charge moving faster than the speed

of light in a medium (for example, glass or water) would emit

a shock wave of electromagnetic radiation; in 1934 Pavel

Cherenkov experimentally discovered the phenomenon, now

called Cherenkov

radiation, for which he won the Nobel Prize in 1958. In

1902, Heaviside applied his theory of transmission lines to the

Earth as a whole and explained the propagation of

radio waves over intercontinental distances as due to a

transmission line formed by conductive seawater and a hypothetical

conductive layer in the upper atmosphere dubbed the

Heaviside

layer. In 1924 Edward V. Appleton confirmed the existence

of such a layer, the ionosphere, and won the Nobel prize in 1947

for the discovery.

Oliver Heaviside never won a Nobel Price, although he was

nominated for the physics prize in 1912. He shouldn't

have felt too bad, though, as other nominees passed over for the

prize that year included Hendrik Lorentz, Ernst Mach,

Max Planck, and Albert Einstein. (The winner that year was

Gustaf Dalén,

“for his invention of automatic regulators for use in

conjunction with gas accumulators for illuminating lighthouses

and buoys”—oh well.) He did receive Britain's

highest recognition for scientific achievement, being named a

Fellow of the Royal Society in 1891. In 1921 he was the first

recipient of the Faraday Medal from the Institution of

Electrical Engineers.

Having never held a job between 1874 and his death in 1925,

Heaviside lived on his irregular income from writing, the

generosity of his family, and, from 1896 onward a pension

of £120 per year (less than his starting salary as a

telegraph operator in 1868) from the Royal Society. He was

a proud man and refused several other offers of money which

he perceived as charity. He turned down an offer of compensation

for his invention of loading coils from AT&T when they

refused to acknowledge his sole responsibility for the invention.

He never married, and in his elder years became somewhat of a

recluse and, although he welcomed visits from other scientists,

hardly ever left his home in Torquay in Devon.

His impact on the physics of electromagnetism and the craft

of electrical engineering can be seen in the list of terms he

coined which are in everyday use: “admittance”,

“conductance”, “electret”,

“impedance”, “inductance”,

“permeability”, “permittance”,

“reluctance”, and “susceptance”. His

work has never been out of print, and sparkles with his

intuition, mathematical prowess, and wicked wit directed at

those he considered pompous or lost in needless abstraction and

rigor. He never sought the limelight and among those upon whose

work much of our present-day technology is founded, he is among

the least known. But as long as electronic technology persists,

it is a monument to the life and work of Oliver Heaviside.

These are not only simpler, condensing twenty equations to

just four, but provide (once you learn the notation and

meanings of the variables) an intuitive sense for what is

going on. This made, for the first time, Maxwell's theory

accessible to working physicists and engineers interested

in getting the answer out rather than spending years

studying an arcane theory. (Vector calculus was

independently invented at the same time by the American

J. Willard Gibbs. Heaviside and Gibbs both acknowledged

the work of the other and there was no priority dispute.

The notation we use today is that of Gibbs, but the

mathematical content of the two formulations is

essentially identical.)

And, during the same decade of the 1880s, Heaviside

invented the

operational

calculus, a method of calculation which reduces the solution

of complicated problems involving differential equations to

simple algebra. Heaviside was able to solve so many problems

which others couldn't because he was using powerful computational

tools they had not yet adopted. The situation was similar to

that of Isaac Newton who was effortlessly solving problems

such as the

brachistochrone

using the calculus he'd invented while his contemporaries

struggled with more cumbersome methods. Some of the things

Heaviside did in the operational calculus, such as cancel

derivative signs in equations and take the square root of a

derivative sign made rigorous mathematicians shudder but, hey,

it worked and that was good enough for Heaviside and the many

engineers and applied mathematicians who adopted his methods.

(In the 1920s, pure mathematicians used the theory of

Laplace transforms

to reformulate the operational calculus in a rigorous manner,

but this was decades after Heaviside's work and long after

engineers were routinely using it in their calculations.)

Heaviside's intuitive grasp of electromagnetism and powerful

computational techniques placed him in the forefront of

exploration of the field. He calculated the electric field of

a moving charged particle and found it contracted in the

direction of motion, foreshadowing the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction

which would figure in Einstein's

special relativity. In 1889

he computed the force on a point charge moving in an electromagnetic

field, which is now called the

Lorentz force

after Hendrik Lorentz who independently discovered it six years

later. He predicted that a charge moving faster than the speed

of light in a medium (for example, glass or water) would emit

a shock wave of electromagnetic radiation; in 1934 Pavel

Cherenkov experimentally discovered the phenomenon, now

called Cherenkov

radiation, for which he won the Nobel Prize in 1958. In

1902, Heaviside applied his theory of transmission lines to the

Earth as a whole and explained the propagation of

radio waves over intercontinental distances as due to a

transmission line formed by conductive seawater and a hypothetical

conductive layer in the upper atmosphere dubbed the

Heaviside

layer. In 1924 Edward V. Appleton confirmed the existence

of such a layer, the ionosphere, and won the Nobel prize in 1947

for the discovery.

Oliver Heaviside never won a Nobel Price, although he was

nominated for the physics prize in 1912. He shouldn't

have felt too bad, though, as other nominees passed over for the

prize that year included Hendrik Lorentz, Ernst Mach,

Max Planck, and Albert Einstein. (The winner that year was

Gustaf Dalén,

“for his invention of automatic regulators for use in

conjunction with gas accumulators for illuminating lighthouses

and buoys”—oh well.) He did receive Britain's

highest recognition for scientific achievement, being named a

Fellow of the Royal Society in 1891. In 1921 he was the first

recipient of the Faraday Medal from the Institution of

Electrical Engineers.

Having never held a job between 1874 and his death in 1925,

Heaviside lived on his irregular income from writing, the

generosity of his family, and, from 1896 onward a pension

of £120 per year (less than his starting salary as a

telegraph operator in 1868) from the Royal Society. He was

a proud man and refused several other offers of money which

he perceived as charity. He turned down an offer of compensation

for his invention of loading coils from AT&T when they

refused to acknowledge his sole responsibility for the invention.

He never married, and in his elder years became somewhat of a

recluse and, although he welcomed visits from other scientists,

hardly ever left his home in Torquay in Devon.

His impact on the physics of electromagnetism and the craft

of electrical engineering can be seen in the list of terms he

coined which are in everyday use: “admittance”,

“conductance”, “electret”,

“impedance”, “inductance”,

“permeability”, “permittance”,

“reluctance”, and “susceptance”. His

work has never been out of print, and sparkles with his

intuition, mathematical prowess, and wicked wit directed at

those he considered pompous or lost in needless abstraction and

rigor. He never sought the limelight and among those upon whose

work much of our present-day technology is founded, he is among

the least known. But as long as electronic technology persists,

it is a monument to the life and work of Oliver Heaviside.

November 2018

- Mahon, Basil.

The Man Who Changed Everything.

Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

ISBN 978-0-470-86171-4.

-

In the 19th century, science in general and physics in particular grew up,

assuming their modern form which is still recognisable today. At the start

of the century, the word “scientist” was not yet in use, and

the natural philosophers of the time were often amateurs. University

research in the sciences, particularly in Britain, was rare. Those

working in the sciences were often occupied by cataloguing natural

phenomena, and apart from Newton's monumental achievements, few people

focussed on discovering mathematical laws to explain the new physical

phenomena which were being discovered such as electricity and magnetism.

One person, James Clerk Maxwell, was largely responsible for creating the

way modern science is done and the way we think about theories of physics,

while simultaneously restoring Britain's standing in physics compared to

work on the Continent, and he created an institution which would continue

to do important work from the time of his early death until the present day.

While every physicist and electrical engineer knows of Maxwell and his

work, he is largely unknown to the general public, and even those who are

aware of his seminal work in electromagnetism may be unaware of the extent

his footprints are found all over the edifice of 19th century physics.

Maxwell was born in 1831 to a Scottish lawyer, John Clerk, and his wife Frances Cay.

Clerk subsequently inherited a country estate, and added “Maxwell”

to his name in honour of the noble relatives from whom he inherited it. His

son's first name, then was “James” and his surname “Clerk Maxwell”:

this is why his full name is always used instead of “James Maxwell”.

From childhood, James was curious about everything he encountered, and instead

of asking “Why?” over and over like many children, he drove his

parents to distraction with “What's the go o' that?”. His father

did not consider science a suitable occupation for his son and tried to direct

him toward the law, but James's curiosity did not extend to legal tomes and

he concentrated on topics that interested him. He published his first

scientific paper, on curves with more than two foci, at the age of 14.

He pursued his scientific education first at the University of Edinburgh

and later at Cambridge, where he graduated in 1854 with a degree in mathematics.

He came in second in the prestigious Tripos examination, earning the title of

Second Wrangler.

Maxwell was now free to begin his independent research, and he turned

to the problem of human colour vision. It had been established that

colour vision worked by detecting the mixture of three primary colours,

but Maxwell was the first to discover that these primaries were red,

green, and blue, and that by mixing them in the correct proportion,

white would be produced. This was a matter to which Maxwell would

return repeatedly during his life.

In 1856 he accepted an appointment as a full professor and department head

at Marischal College, in Aberdeen Scotland. In 1857, the topic for the

prestigious Adams Prize was the nature of the rings of Saturn. Maxwell's

submission was a tour de force which

proved that the rings could not be either solid nor a liquid, and hence

had to be made of an enormous number of individually orbiting bodies.

Maxwell was awarded the prize, the significance of which was magnified

by the fact that his was the only submission: all of the others who

aspired to solve the problem had abandoned it as too difficult.

Maxwell's next post was at King's College London, where he investigated

the properties of gases and strengthened the evidence for the molecular

theory of gases. It was here that he first undertook to explain the

relationship between electricity and magnetism which had been discovered

by Michael Faraday. Working in the old style of physics, he constructed

an intricate mechanical thought experiment model which might explain the

lines of force that Faraday had introduced but which many scientists

thought were mystical mumbo-jumbo. Maxwell believed the alternative

of action at a distance without any intermediate mechanism was

wrong, and was able, with his model, to explain the phenomenon of

rotation of the plane of polarisation of light by a magnetic field,

which had been discovered by Faraday. While at King's College, to

demonstrate his theory of colour vision, he took and displayed the

first colour photograph.

Maxwell's greatest scientific achievement was done while living the life

of a country gentleman at his estate, Glenair. In his textbook,

A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, he presented

his

famous equations

which showed that electricity and magnetism were

two aspects of the same phenomenon. This was the first of the great unifications

of physical laws which have continued to the present day. But that isn't

all they showed. The speed of light appeared as a conversion factor between

the units of electricity and magnetism, and the equations allowed solutions

of waves oscillating between an electric and magnetic field which could

propagate through empty space at the speed of light. It was compelling

to deduce that light was just such an electromagnetic wave, and that

waves of other frequencies outside the visual range must exist. Thus

was laid the foundation of wireless communication, X-rays, and gamma rays.

The speed of light is a constant in Maxwell's equations, not depending upon

the motion of the observer. This appears to conflict with Newton's laws

of mechanics, and it was not until Einstein's 1905 paper on

special relativity

that the mystery would be resolved. In essence, faced with a dispute between

Newton and Maxwell, Einstein decided to bet on Maxwell, and he chose wisely.

Finally, when you look at Maxwell's equations (in their modern form, using

the notation of vector calculus), they appear lopsided. While they unify

electricity and magnetism, the symmetry is imperfect in that while a moving

electric charge generates a magnetic field, there is no magnetic charge which,

when moved, generates an electric field. Such a charge would be a

magnetic monopole,

and despite extensive experimental searches, none has ever been found. The

existence of monopoles would make Maxwell's equations even more beautiful, but

sometimes nature doesn't care about that. By all evidence to date, Maxwell got it

right.

In 1871 Maxwell came out of retirement to accept a professorship at Cambridge

and found the

Cavendish Laboratory,

which would focus on experimental science and elevate Cambridge to world-class

status in the field. To date, 29 Nobel Prizes have been awarded for work done

at the Cavendish.

Maxwell's theoretical and experimental work on heat and gases revealed

discrepancies which were not explained until the development of quantum

theory in the 20th century. His suggestion of

Maxwell's demon

posed a deep puzzle in the foundations of thermodynamics which eventually,

a century later, showed the deep connections between information theory

and statistical mechanics. His practical work on automatic governors for

steam engines foreshadowed what we now call control theory. He played a key

part in the development of the units we use for electrical quantities.

By all accounts Maxwell was a modest, generous, and well-mannered man. He

wrote whimsical poetry, discussed a multitude of topics (although he had little

interest in politics), was an enthusiastic horseman and athlete (he would swim

in the sea off Scotland in the winter), and was happily married, with his wife

Katherine an active participant in his experiments. All his life, he supported

general education in science, founding a working men's college in Cambridge and

lecturing at such colleges throughout his career.

Maxwell lived only 48 years—he died in 1879 of the same cancer which had

killed his mother when he was only eight years old. When he fell ill, he was

engaged in a variety of research while presiding at the Cavendish Laboratory.

We shall never know what he might have done had he been granted another two

decades.

Apart from the significant achievements Maxwell made in a wide variety of

fields, he changed the way physicists look at, describe, and think about

natural phenomena. After using a mental model to explore electromagnetism,

he discarded it in favour of a mathematical description of its behaviour.

There is no theory behind Maxwell's equations: the equations are

the theory. To the extent they produce the correct results when

experimental conditions are plugged in, and predict new phenomena which

are subsequently confirmed by experiment, they are valuable. If they

err, they should be supplanted by something more precise. But they say

nothing about what is really going on—they only seek to

model what happens when you do experiments. Today, we are so accustomed

to working with theories of this kind: quantum mechanics, special and general

relativity, and the standard model of particle physics, that we don't think

much about it, but it was revolutionary in Maxwell's time. His mathematical

approach, like Newton's, eschewed explanation in favour of prediction: “We

have no idea how it works, but here's what will happen if you do this experiment.”

This is perhaps Maxwell's greatest legacy.

This is an excellent scientific biography of Maxwell which also gives the reader

a sense of the man. He was such a quintessentially normal person there aren't

a lot of amusing anecdotes to relate. He loved life, loved his work, cherished his

friends, and discovered the scientific foundations of the technologies which

allow you to read this. In the

Kindle edition, at least as read on an iPad, the text

appears in a curious, spidery, almost vintage, font in which periods are difficult to

distinguish from commas. Numbers sometimes have spurious spaces embedded within them,

and the index cites pages in the print edition which are useless since the Kindle

edition does not include real page numbers.

August 2014