« Investing: Euro-denominated sovereign debt |

Main

| Reading List: What's So Great About Christianity »

Monday, March 17, 2008

Investing: The ultimate refuge

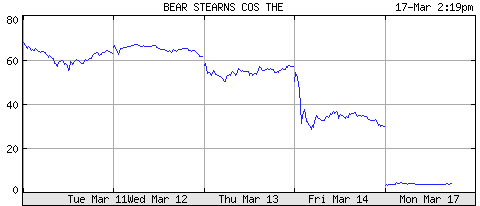

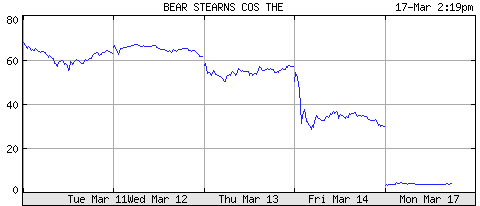

Take a look at this five day chart for Bear Stearns, which traded as high as 159 dollars a share within the last year, and was gobbled up by JP Morgan Chase for $2 per share yesterday, following the “rescue” announced earlier. That represents a drop in valuation by 96% compared to the price at the close of trading last Thursday.

This illustrates an unpleasant fact about investing, especially in a time of financial turmoil: with any paper asset

you can lose everything—your stock can suddenly flatline like Bear Stearns when some surprise hits the market; your bond may become worthless when its issuer goes bankrupt, and even paper money may lose its value due to inflation or the imposition of exchange controls or suspension of convertibility by the issuing government.

Now, collapses of these kinds are rare and improbable circumstances, but it's the increasing likelihood of such calamities which defines eras of financial peril. The usual defence against such disasters is diversification: across issuers, industries, currencies, types of securities, and nations; part of your portfolio may get hit, but the rest will probably ride out the storm. As I mentioned in the

last gnome-o-gram, in a full-fledged financial crisis, almost everybody loses, and he who loses the least ends up in the best comparative position at the end. While diversification can mitigate the impact of an isolated default, it may not help in the kind of chain-reaction collapse which occurred in the 1929–1932 period, where each successive default wiped out assets of other institutions, tipping more and more into insolvency. If it weren't for worries about such a scenario happening today, you wouldn't see the U.S. Federal Reserve rushing in to keep Bear Stearns from going bust (although if you're a shareholder, the distinction may not appear to be that great).

So, given a really dire worst-case scenario, is there

any asset you can hold which

won't go to zero if the whole financial fairy castle goes

blooie. Yes, there is, and that's where the “barbaric relic”, gold, comes in. If you start looking up gold investment on the Internet, you will come across a multitude of “gold bug” sites which, in language as impassioned as it is ungrammatical, exhorts readers to load up on gold in order to reap profits beyond the dreams of avarice when the impending collapse of civilisation eventuates. This, to my mind, is

precisely the wrong way to think about gold as an investment. Gold is an asset with

intrinsic value: it is expensive to mine, and the quantity mined in any given year is minuscule compared to the quantity already above ground. Certainly gold fluctuates with supply and demand like any other commodity in a free market: in 1980 an ounce of gold peaked at in excess of $800 and by 1999 it had fallen to about $250 (

long term chart), but at no time in human history has it ever gone to zero, and unless somebody invents a cheap way to transmute elements, it never will. In fact, if you average over a period long enough to smooth out the speculative booms and busts and exclude episodes of distortion of market forces by government intervention, the purchasing power of gold has remained about the same from the time of the Babylonian empire to the present day.

Consequently, gold is first and foremost a

store of value; it's a foundational asset which may appreciate or decline, but

can't go to zero, and in a widespread collapse which causes drastic depreciation of all kinds of paper instruments, it will, simply, by retaining its value, appreciate on a relative basis. Thus, one shouldn't think of buying gold in order to

make money, but rather as a way to

avoid losing money—it's the part of your portfolio you can always rely upon to be worth something, regardless of what happens to the rest. (This is not to say that one can't trade gold with the goal of speculative profits, just like any other commodity, but that's not what I'm discussing here.)

Aside from its function as an store of inherent value, gold is an otherwise crummy investment. Not only does it not pay interest, in most forms

you have to pay storage and insurance charges just to hold it. If you keep it in physical form, you have to worry about it being stolen. In countries like the United States, which tax “capital gains” on sales of appreciated assets, gold is often exempted from tax preferences which apply to stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments. And finally, even though you may keep telling yourself that you own the gold for its intrinsic value, it may be difficult to ignore the day to day fluctuations in the price of gold.

Given these drawbacks, I believe the answer to the question “how much gold should I own” should be “as little as possible” (again, we're not talking about speculation here, just a foundation position you do not trade), balanced by the consideration that “it's enough that I'd be happy to be left with if everything else goes to zero”. Obviously, this is a judgement every investor must make based upon their own personal circumstances. But note that answering these questions does not involve any forecast of economic or market conditions whatsoever. The gold is there precisely because you

don't know what tomorrow is going to bring, or what it may do to the rest of your portfolio; the gold is what you know you'll be left with regardless of whatever may happen.

In the next gnome-o-gram, I'll discuss various ways of including gold in a portfolio. Meanwhile,

learn why it's yellow.

Other gnome-o-grams

Posted at March 17, 2008 20:01