« Reading List: Starship Grifters | Main | Gnome-o-gram: Experts »

Sunday, February 4, 2018

Reading List: Life 3.0

- Tegmark, Max. Life 3.0. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. ISBN 978-1-101-94659-6.

-

The Earth formed from the protoplanetary disc surrounding the

young Sun around 4.6 billion years ago. Around one hundred

million years later, the nascent planet, beginning to solidify,

was clobbered by a giant impactor which ejected the mass that

made the Moon. This impact completely re-liquefied the Earth and

Moon. Around 4.4 billion years ago, liquid water appeared on

the Earth's surface (evidence for this comes from

Hadean

zircons which date from this era).

And, some time thereafter, just about as soon as the Earth

became environmentally hospitable to life (lack of disruption

due to bombardment by comets and asteroids, and a temperature

range in which the chemical reactions of life can proceed),

life appeared. In speaking of the origin of life, the evidence

is subtle and it's hard to be precise. There is completely

unambiguous evidence of life on Earth 3.8 billion years ago, and

more subtle clues that life may have existed as early as 4.28

billion years before the present. In any case, the Earth has

been home to life for most of its existence as a planet.

This was what the author calls “Life 1.0”. Initially

composed of single-celled organisms (which, nonetheless, dwarf

in complexity of internal structure and chemistry anything

produced by other natural processes or human technology to this

day), life slowly diversified and organised into colonies of

identical cells, evidence for which can be seen in

rocks

today.

About half a billion years ago, taking advantage of the far more

efficient metabolism permitted by the oxygen-rich atmosphere

produced by the simple organisms which preceded them, complex

multi-cellular creatures sprang into existence in the

“Cambrian

explosion”. These critters manifested all

the body forms found today, and every living being traces

its lineage back to them. But they were still Life 1.0.

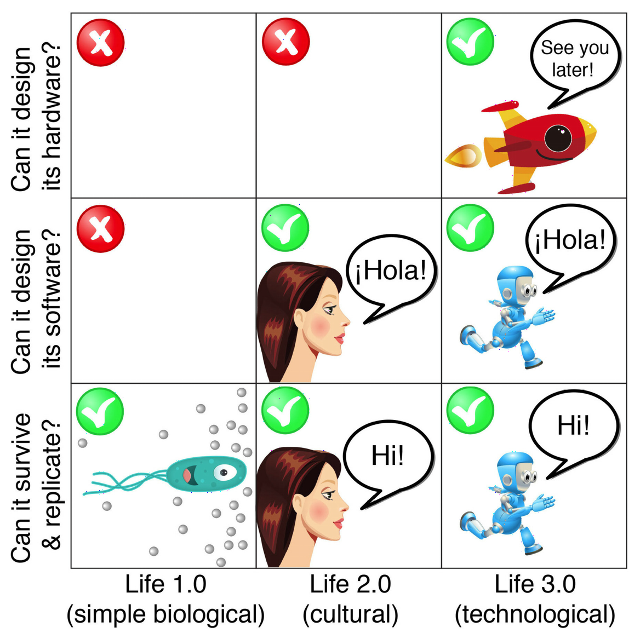

What is Life 1.0? Its key characteristics are that it can

metabolise and reproduce, but that it can learn only

through evolution. Life 1.0, from bacteria through insects,

exhibits behaviour which can be quite complex, but that

behaviour can be altered only by the random variation of

mutations in the genetic code and natural selection of

those variants which survive best in their environment. This

process is necessarily slow, but given the vast expanses of

geological time, has sufficed to produce myriad species,

all exquisitely adapted to their ecological niches.

To put this in present-day computer jargon, Life 1.0 is

“hard-wired”: its hardware (body plan and metabolic

pathways) and software (behaviour in response to stimuli) are

completely determined by its genetic code, and can be altered

only through the process of evolution. Nothing an organism

experiences or does can change its genetic programming: the

programming of its descendants depends solely upon its success

or lack thereof in producing viable offspring and the luck of

mutation and recombination in altering the genome they inherit.

Much more recently, Life 2.0 developed. When? If you want

to set a bunch of paleontologists squabbling, simply ask them

when learned behaviour first appeared, but some time between

the appearance of the first mammals and the ancestors of

humans, beings developed the ability to learn from

experience and alter their behaviour accordingly. Although

some would argue simpler creatures (particularly

birds)

may do this, the fundamental hardware which seems to enable

learning is the

neocortex,

which only mammalian brains possess. Modern humans are the

quintessential exemplars of Life 2.0; they not only learn from

experience, they've figured out how to pass what they've learned

to other humans via speech, writing, and more recently, YouTube

comments.

While Life 1.0 has hard-wired hardware and software, Life 2.0 is

able to alter its own software. This is done by training the

brain to respond in novel ways to stimuli. For example, you're

born knowing no human language. In childhood, your brain

automatically acquires the language(s) you hear from those

around you. In adulthood you may, for example, choose to learn

a new language by (tediously) training your brain to understand,

speak, read, and write that language. You have deliberately

altered your own software by reprogramming your brain, just as

you can cause your mobile phone to behave in new ways by

downloading a new application. But your ability to change

yourself is limited to software. You have to work with the

neurons and structure of your brain. You might wish to have

more or better memory, the ability to see more colours (as some

insects do), or run a sprint as fast as the current Olympic

champion, but there is nothing you can do to alter those

biological (hardware) constraints other than hope, over many

generations, that your descendants might evolve those

capabilities. Life 2.0 can design (within limits) its software,

but not its hardware.

The emergence of a new major revision of life is a big

thing. In 4.5 billion years, it has only happened twice,

and each time it has remade the Earth. Many technologists

believe that some time in the next century (and possibly

within the lives of many reading this review) we may see

the emergence of Life 3.0. Life 3.0, or Artificial

General Intelligence (AGI), is machine intelligence,

on whatever technological substrate, which can perform

as well as or better than human beings, all of the

intellectual tasks which they can do. A Life 3.0 AGI

will be better at driving cars, doing scientific research,

composing and performing music, painting pictures,

writing fiction, persuading humans and other AGIs to

adopt its opinions, and every other task including,

most importantly, designing and building ever more capable

AGIs. Life 1.0 was hard-wired; Life 2.0 could alter its

software, but not its hardware; Life 3.0 can alter both

its software and hardware. This may set off an

“intelligence

explosion” of recursive

improvement, since each successive generation of AGIs will be

even better at designing more capable successors, and this cycle

of refinement will not be limited to the glacial timescale of

random evolutionary change, but rather an engineering cycle

which will run at electronic speed. Once the AGI train pulls

out of the station, it may develop from the level of human

intelligence to something as far beyond human cognition as

humans are compared to ants in one human sleep cycle. Here is a

summary of Life 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0.

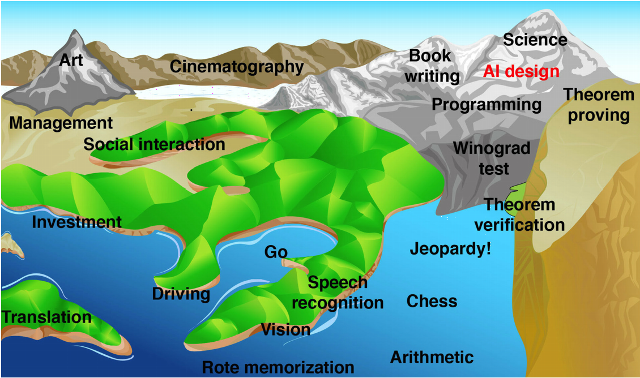

The emergence of Life 3.0 is something about which we, exemplars of Life 2.0, should be concerned. After all, when we build a skyscraper or hydroelectric dam, we don't worry about, or rarely even consider, the multitude of Life 1.0 organisms, from bacteria through ants, which may perish as the result of our actions. Might mature Life 3.0, our descendants just as much as we are descended from Life 1.0, be similarly oblivious to our fate and concerns as it unfolds its incomprehensible plans? As artificial intelligence researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky puts it, “The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” Or, as Max Tegmark observes here, “[t]he real worry isn't malevolence, but competence”. It's unlikely a super-intelligent AGI would care enough about humans to actively exterminate them, but if its goals don't align with those of humans, it may incidentally wipe them out as it, for example, disassembles the Earth to use its core for other purposes. But isn't this all just science fiction—scary fairy tales by nerds ungrounded in reality? Well, maybe. What is beyond dispute is that for the last century the computing power available at constant cost has doubled about every two years, and this trend shows no evidence of abating in the near future. Well, that's interesting, because depending upon how you estimate the computational capacity of the human brain (a contentious question), most researchers expect digital computers to achieve that capacity within this century, with most estimates falling within the years from 2030 to 2070, assuming the exponential growth in computing power continues (and there is no physical law which appears to prevent it from doing so). My own view of the development of machine intelligence is that of the author in this “intelligence landscape”.

Altitude on the map represents the difficulty of a cognitive task. Some tasks, for example management, may be relatively simple in and of themselves, but founded on prerequisites which are difficult. When I wrote my first computer program half a century ago, this map was almost entirely dry, with the water just beginning to lap into rote memorisation and arithmetic. Now many of the lowlands which people confidently said (often not long ago), “a computer will never…”, are submerged, and the ever-rising waters are reaching the foothills of cognitive tasks which employ many “knowledge workers” who considered themselves safe from the peril of “automation”. On the slope of Mount Science is the base camp of AI Design, which is shown in red since when the water surges into it, it's game over: machines will now be better than humans at improving themselves and designing their more intelligent and capable successors. Will this be game over for humans and, for that matter, biological life on Earth? That depends, and it depends upon decisions we may be making today. Assuming we can create these super-intelligent machines, what will be their goals, and how can we ensure that our machines embody them? Will the machines discard our goals for their own as they become more intelligent and capable? How would bacteria have solved this problem contemplating their distant human descendants? First of all, let's assume we can somehow design our future and constrain the AGIs to implement it. What kind of future will we choose? That's complicated. Here are the alternatives discussed by the author. I've deliberately given just the titles without summaries to stimulate your imagination about their consequences.

- Libertarian utopia

- Benevolent dictator

- Egalitarian utopia

- Gatekeeper

- Protector god

- Enslaved god

- Conquerors

- Descendants

- Zookeeper

- 1984

- Reversion

- Self-destruction

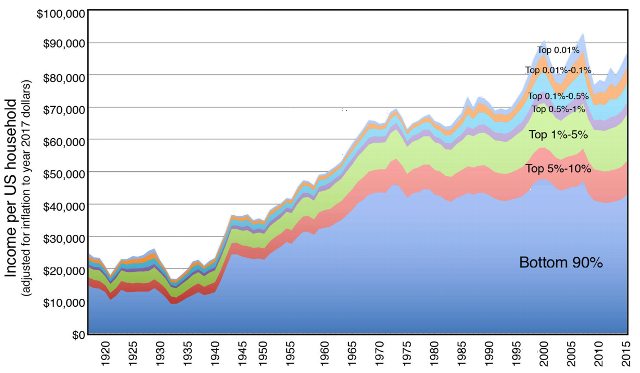

I'm not sure this chart supports the argument that technology has been the principal cause for the stagnation of income among the bottom 90% of households since around 1970. There wasn't any major technological innovation which affected employment that occurred around that time: widespread use of microprocessors and personal computers did not happen until the 1980s when the flattening of the trend was already well underway. However, two public policy innovations in the United States which occurred in the years immediately before 1970 (1, 2) come to mind. You don't have to be an MIT cosmologist to figure out how they torpedoed the rising trend of prosperity for those aspiring to better themselves which had characterised the U.S. since 1940. Nonetheless, what is coming down the track is something far more disruptive than the transition from an agricultural society to industrial production, and it may happen far more rapidly, allowing less time to adapt. We need to really get this right, because everything depends on it. Observation and our understanding of the chemistry underlying the origin of life is compatible with Earth being the only host to life in our galaxy and, possibly, the visible universe. We have no idea whatsoever how our form of life emerged from non-living matter, and it's entirely possible it may have been an event so improbable we'll never understand it and which occurred only once. If this be the case, then what we do in the next few decades matters even more, because everything depends upon us, and what we choose. Will the universe remain dead, or will life burst forth from this most improbable seed to carry the spark born here to ignite life and intelligence throughout the universe? It could go either way. If we do nothing, life on Earth will surely be extinguished: the death of the Sun is certain, and long before that the Earth will be uninhabitable. We may be wiped out by an asteroid or comet strike, by a dictator with his fat finger on a button, or by accident (as Nathaniel Borenstein said, “The most likely way for the world to be destroyed, most experts agree, is by accident. That's where we come in; we're computer professionals. We cause accidents.”). But if we survive these near-term risks, the future is essentially unbounded. Life will spread outward from this spark on Earth, from star to star, galaxy to galaxy, and eventually bring all the visible universe to life. It will be an explosion which dwarfs both its predecessors, the Cambrian and technological. Those who create it will not be like us, but they will be our descendants, and what they achieve will be our destiny. Perhaps they will remember us, and think kindly of those who imagined such things while confined to one little world. It doesn't matter; like the bacteria and ants, we will have done our part. The author is co-founder of the Future of Life Institute which promotes and funds research into artificial intelligence safeguards. He guided the development of the Asilomar AI Principles, which have been endorsed to date by 1273 artificial intelligence and robotics researchers. In the last few years, discussion of the advent of AGI and the existential risks it may pose and potential ways to mitigate them has moved from a fringe topic into the mainstream of those engaged in developing the technologies moving toward that goal. This book is an excellent introduction to the risks and benefits of this possible future for a general audience, and encourages readers to ask themselves the difficult questions about what future they want and how to get there. In the Kindle edition, everything is properly linked. Citations of documents on the Web are live links which may be clicked to display them. There is no index.

Posted at February 4, 2018 13:54