- Anonymous Conservative [Michael Trust].

The Evolutionary Psychology Behind Politics.

Macclenny, FL: Federalist Publications, [2012, 2014] 2017.

ISBN 978-0-9829479-3-7.

-

One of the puzzles noted by observers of the contemporary

political and cultural scene is the division of the population

into two factions, (called in the sloppy terminology of the

United States) “liberal” and “conservative”,

and that if you pick a member from either faction by

observing his or her position on one of the divisive issues

of the time, you can, with a high probability of accuracy,

predict their preferences on all of a long list of other issues

which do not, on the face of it, seem to have very much to do

with one another. For example, here is a list of present-day

hot-button issues, presented in no particular order.

- Health care, socialised medicine

- Climate change, renewable energy

- School choice

- Gun control

- Higher education subsidies, debt relief

- Free speech (hate speech laws, Internet censorship)

- Deficit spending, debt, and entitlement reform

- Immigration

- Tax policy, redistribution

- Abortion

- Foreign interventions, military spending

What a motley collection of topics! About the only thing they

have in common is that the omnipresent administrative

super-state has become involved in them in one way or another,

and therefore partisans of policies affecting them view it

important to influence the state's action in their regard. And

yet, pick any one, tell me what policies you favour, and I'll

bet I can guess at where you come down on at least eight of the

other ten. What's going on?

Might there be some deeper, common thread or cause which

explains this otherwise curious clustering of opinions? Maybe

there's something rooted in biology, possibly even heritable,

which predisposes people to choose the same option on disparate

questions? Let's take a brief excursion into ecological

modelling and see if there's something of interest there.

As with all modelling, we start with a simplified, almost

cartoon abstraction of the gnarly complexity of the real world.

Consider a closed territory (say, an island) with abundant

edible vegetation and no animals. Now introduce a species, such

as rabbits, which can eat the vegetation and turn it into more

rabbits. We start with a small number, P, of rabbits.

Now, once they get busy with bunny business, the population will

expand at a rate r which is essentially constant over a

large population. If r is larger than 1 (which for

rabbits it will be, with litter sizes between 4 and 10 depending on

the breed, and gestation time around a month) the population

will increase. Since the rate of increase is constant and the

total increase is proportional to the size of the existing

population, this growth will be exponential. Ask any

Australian.

Now, what will eventually happen? Will the island disappear under

a towering pile of rabbits inexorably climbing to the top of

the atmosphere? No—eventually the number of rabbits will

increase to the point where they are eating all the

vegetation the territory can produce. This number, K,

is called the “carrying capacity” of the environment,

and it is an absolute number for a given species and environment. This

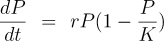

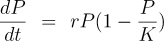

can be expressed as a differential equation called the

Verhulst

model, as follows:

It's a maxim among popular science writers that every equation

you include cuts your readership by a factor of two, so among

the hardy half who remain, let's see how this works. It's really

very simple (and indeed, far simpler than actual population

dynamics in a real environment). The left side,

“dP/dt” simply means “the rate of growth

of the population P with respect to time, t”.

On the right hand side, “rP” accounts for the

increase (or decrease, if r is less than 0) in population,

proportional to the current population. The population is limited

by the carrying capacity of the habitat, K, which is

modelled by the factor “(1 − P/K)”.

Now think about how this works: when the population is very small,

P/K will be close to zero and, subtracted from one,

will yield a number very close to one. This, then, multiplied by

the increase due to rP will have little effect and the

growth will be largely unconstrained. As the population P

grows and begins to approach K, however, P/K

will approach unity and the factor will fall to zero, meaning that

growth has completely stopped due to the population reaching

the carrying capacity of the environment—it simply doesn't

produce enough vegetation to feed any more rabbits. If the rabbit

population overshoots, this factor will go negative and there will

be a die-off which eventually brings the population P

below the carrying capacity K. (Sorry if this seems

tedious; one of the great things about learning even a very little

about differential equations is that all of this is apparent at a

glance from the equation once you get over the speed bump of

understanding the notation and algebra involved.)

This is grossly over-simplified. In fact, real populations are

prone to oscillations and even chaotic dynamics, but we don't

need to get into any of that for what follows, so I won't.

Let's complicate things in our bunny paradise by introducing a

population of wolves. The wolves can't eat the vegetation, since

their digestive systems cannot extract nutrients from it, so

their only source of food is the rabbits. Each wolf eats many

rabbits every year, so a large rabbit population is required to

support a modest number of wolves. Now if we go back and look

at the equation for wolves, K represents the number of

wolves the rabbit population can sustain, in the steady state,

where the number of rabbits eaten by the wolves just balances

the rabbits' rate of reproduction. This will often result in

a rabbit population smaller than the carrying capacity

of the environment, since their population is now constrained

by wolf predation and not K.

What happens as this (oversimplified) system cranks away,

generation after generation, and Darwinian evolution kicks in?

Evolution consists of two processes: variation, which is largely

random, and selection, which is sensitively dependent upon the

environment. The rabbits are unconstrained by K, the

carrying capacity of their environment. If their numbers

increase beyond a population P substantially smaller

than K, the wolves will simply eat more of them and

bring the population back down. The rabbit population, then, is

not at all constrained by K, but rather by r:

the rate at which they can produce new offspring. Population

biologists call this an r-selected species: evolution

will select for individuals who produce the largest number of

progeny in the shortest time, and hence for a life cycle which

minimises parental investment in offspring and against mating

strategies, such as lifetime pair bonding, which would limit

their numbers. Rabbits which produce fewer offspring will lose

a larger fraction of them to predation (which affects all

rabbits, essentially at random), and the genes which they carry

will be selected out of the population. An r-selected

population, sometimes referred to as

r-strategists, will tend to be small, with short

gestation time, high fertility (offspring per litter), rapid

maturation to the point where offspring can reproduce, and broad

distribution of offspring within the environment.

Wolves operate under an entirely different set of constraints.

Their entire food supply is the rabbits, and since it takes a

lot of rabbits to keep a wolf going, there will be fewer wolves

than rabbits. What this means, going back to the Verhulst

equation, is that the 1 − P/K

factor will largely determine their population: the carrying

capacity K of the environment supports a much smaller

population of wolves than their food source, rabbits, and if

their rate of population growth r were to increase, it

would simply mean that more wolves would starve due to

insufficient prey. This results in an entirely different set of

selection criteria driving their evolution: the wolves are said

to be K-selected or K-strategists. A

successful wolf (defined by evolution theory as more likely to

pass its genes on to successive generations) is not one which

can produce more offspring (who would merely starve by hitting

the K limit before reproducing), but rather highly

optimised predators, able to efficiently exploit the limited

supply of rabbits, and to pass their genes on to a small number

of offspring, produced infrequently, which require substantial

investment by their parents to train them to hunt and,

in many cases, acquire social skills to act as part of a group

that hunts together. These K-selected species tend to

be larger, live longer, have fewer offspring, and have parents

who spend much more effort raising them and training them to be

successful predators, either individually or as part of a pack.

“K or r, r or K:

once you've seen it, you can't look away.”

Just as our island of bunnies and wolves was over-simplified,

the dichotomy of r- and K-selection is rarely

precisely observed in nature (although rabbits and wolves are

pretty close to the extremes, which it why I chose them). Many

species fall somewhere in the middle and, more importantly,

are able to shift their strategy on the fly, much faster than

evolution by natural selection, based upon the availability of

resources. These r/K shape-shifters react to

their environment. When resources are abundant, they adopt an

r-strategy, but as their numbers approach the carrying

capacity of their environment, shift to life cycles

you'd expect from K-selection.

What about humans? At a first glance, humans would seem to be

a quintessentially K-selected species. We are

large, have long lifespans (about twice as long as we

“should” based upon the number of heartbeats per

lifetime of other mammals), usually only produce one child (and

occasionally two) per gestation, with around a one year turn-around

between children, and massive investment by parents in

raising infants to the point of minimal autonomy and many

additional years before they become fully functional adults. Humans

are “knowledge workers”, and whether they are

hunter-gatherers, farmers, or denizens of cubicles at The

Company, live largely by their wits, which are a combination

of the innate capability of their hypertrophied brains and

what they've learned in their long apprenticeship through

childhood. Humans are not just predators on what they

eat, but also on one another. They fight, and they fight in

bands, which means that they either develop the social

skills to defend themselves and meet their needs by raiding

other, less competent groups, or get selected out in the

fullness of evolutionary time.

But humans are also highly adaptable. Since modern humans

appeared some time between fifty and two hundred thousand years

ago they have survived, prospered, proliferated, and spread

into almost every habitable region of the Earth. They have

been hunter-gatherers, farmers, warriors, city-builders,

conquerors, explorers, colonisers, traders, inventors,

industrialists, financiers, managers, and, in the

Final Days

of their species, WordPress site administrators.

In many species, the selection of a predominantly r

or K strategy is a mix of genetics and switches

that get set based upon experience in the environment. It is

reasonable to expect that humans, with their large brains and

ability to override inherited instinct, would be

especially sensitive to signals directing them to one or

the other strategy.

Now, finally, we get back to politics. This was a post about

politics. I hope you've been thinking about it as we spent

time in the island of bunnies and wolves, the cruel realities

of natural selection, and the arcana of differential equations.

What does r-selection produce in a human

population? Well, it might, say, be averse to competition

and all means of selection by measures of performance. It would

favour the production of large numbers of offspring at an

early age, by early onset of mating, promiscuity, and

the raising of children by single mothers with minimal

investment by them and little or none by the fathers (leaving

the raising of children to the State). It would welcome

other r-selected people into the community, and

hence favour immigration from heavily r populations.

It would oppose any kind of selection based upon performance,

whether by intelligence tests, academic records, physical

fitness, or job performance. It would strive to create the

ideal r environment of unlimited resources,

where all were provided all their basic needs without having

to do anything but consume. It would oppose and be repelled

by the K component of the population, seeking to

marginalise it as toxic, privileged, or

exploiters of the real people. It might

even welcome conflict with K warriors of adversaries

to reduce their numbers in otherwise pointless foreign adventures.

And K-troop? Once a society in which they initially

predominated creates sufficient wealth to support a burgeoning

r population, they will find themselves outnumbered and

outvoted, especially once the r wave removes the

firebreaks put in place when K was king to guard

against majoritarian rule by an urban underclass. The

K population will continue to do what they do best:

preserving the institutions and infrastructure which sustain

life, defending the society in the military, building and

running businesses, creating the basic science and technologies

to cope with emerging problems and expand the human potential,

and governing an increasingly complex society made up, with

every generation, of a population, and voters, who are

fundamentally unlike them.

Note that the r/K model completely explains

the “crunchy to soggy” evolution of societies

which has been remarked upon since antiquity. Human

societies always start out, as our genetic heritage predisposes

us to, K-selected. We work to better our condition

and turn our large brains to problem-solving and, before

long, the privation our ancestors endured turns into

a pretty good life and then, eventually, abundance. But

abundance is what selects for the r strategy. Those

who would not have reproduced, or have as many children in

the K days of yore, now have babies-a-poppin' as in

the introduction to

Idiocracy,

and before long, not waiting for genetics to do its inexorable

work, but purely by a shift in incentives, the rs outvote

the Ks and the Ks begin to count the days until

their society runs out of the wealth which can be plundered

from them.

But recall that equation. In our simple bunnies and wolves

model, the resources of the island were static. Nothing the

wolves could do would increase K and permit a larger

rabbit and wolf population. This isn't the case for humans.

K humans dramatically increase the carrying capacity of

their environment by inventing new technologies such as

agriculture, selective breeding of plants and animals,

discovering and exploiting new energy sources such as firewood,

coal, and petroleum, and exploring and settling new territories

and environments which may require their discoveries to render

habitable. The rs don't do these things. And as the

rs predominate and take control, this momentum stalls

and begins to recede. Then the hard times ensue. As

Heinlein said many years ago, “This

is known as bad luck.”

And then the

Gods

of the Copybook Headings will, with terror and slaughter return.

And K-selection will, with them, again assert itself.

Is this a complete model, a Rosetta stone for human behaviour? I

think not: there are a number of things it doesn't explain, and

the shifts in behaviour based upon incentives are much too fast

to account for by genetics. Still, when you look at those eleven

issues I listed so many words ago through the r/K

perspective, you can almost immediately see how each strategy maps

onto one side or the other of each one, and they are consistent with

the policy preferences of “liberals” and

“conservatives”. There is also some rather fuzzy

evidence for genetic differences (in particular the

DRD4-7R

allele of the dopamine receptor and size of the right brain

amygdala) which

appear to correlate with ideology.

Still, if you're on one side of the ideological divide and

confronted with somebody on the other and try to argue

from facts and logical inference, you may end up throwing up

your hands (if not your breakfast) and saying, “They

just don't get it!” Perhaps they don't.

Perhaps they can't. Perhaps there's a difference

between you and them as great as that between rabbits and

wolves, which can't be worked out by predator and prey sitting

down and voting on what to have for dinner. This may not be

a hopeful view of the political prospect in the near future,

but hope is not a strategy and to survive and prosper requires

accepting reality as it is and acting accordingly.

December 2019